Goodbye Gilboa: How NYC Drowned an Upstate Town (& Why the Scars Still Run Deep)

Discover the story of Gilboa, once Schoharie County’s largest village, lost to New York City’s water supply. Rediscovered century-old footage, local memories, and fossil finds reveal how this Upstate NY town survived in history.

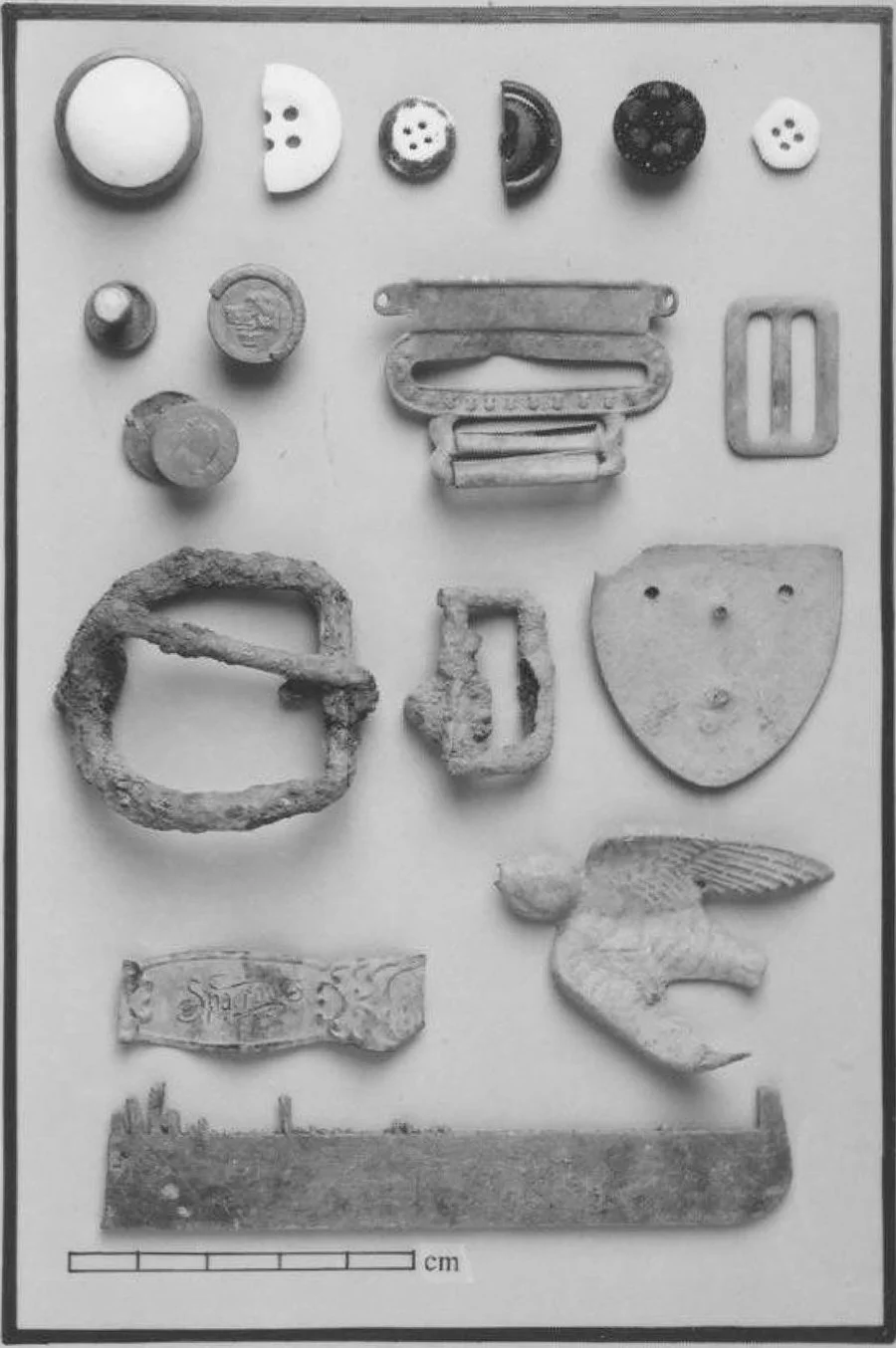

A hundred years after New York City destroyed and flooded the Village of Gilboa to quench its thirst for water, locals still talk about it like it happened yesterday. In a way, it did. Until 9/11—when NYC cracked down on reservoir access—you could still slip down to old Gilboa and walk its paved streets, collecting broken shards of dinner plates, tea cups minus their handles, empty picture frames. All left behind when the water came.

Now, thanks to rediscovered Fox News footage and some historical detective work, the Gilboa Historical Society has created something remarkable: a six-minute silent newsreel bringing the village's final days back to life. Stonemasons and workmen long dead move through their once-bustling community. It's a window into the City's endless need for water—and its cost upstate.

"There are just so many layers," says Lee Hudson, one of the researchers behind the project. "The more you look, the more you learn."

A Last-Minute Betrayal

Gilboa wasn't supposed to be the target. The plan—going back to 1905—was the Prattsville Reservoir. But NYC realized it could get more water by moving the dam just a little north. Gilboa got the devastating news just before Christmas 1915. A map dated December 21 showed the target had shifted. Within a decade, what was once the largest village in Schoharie County—with schools, churches, farms, shops, and hundreds of homes—would be gone.

Found Footage, Incredible Stories

The newsreel's backstory starts with a chance email alerting the Gilboa Historical Society to archival footage at the University of South Carolina's Moving Image Research Collection.

"There are lots of still photos," Hudson said, "but no one had ever seen moving images. We held our breath. And when we went online, it was just as promised: scenes of the village and the dam's construction."

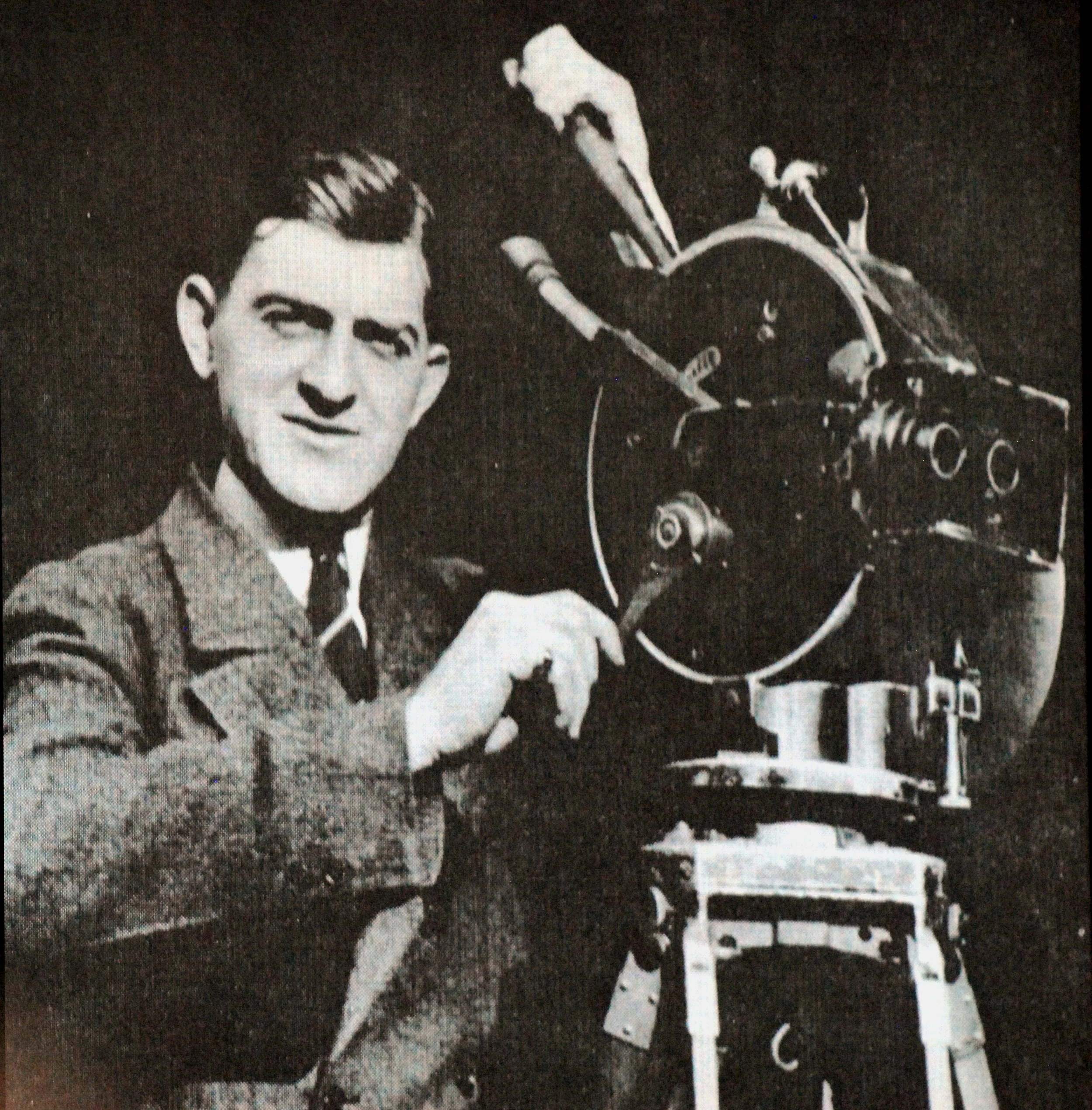

The 1925 footage was shot by "dare devil" cameraman Jack Painter, whose "dope sheets"—shot-by-shot lists of everything he recorded—helped researchers confirm they had it all. Painter's reputation? He'd do anything for a shot.

Then they got greedy. "We thought maybe there's more, from other cameramen." There was.

Earlier footage—misfiled under Ashokan Reservoir, another downstate water grab—captured cameraman Alan Brick documenting the discovery of 385-million-year-old Devonian fossilized trees during construction. They're now recognized as among the oldest on Earth and displayed outside Gilboa Town Hall.

If Painter was a daredevil, Brick was legendary: He shot the only footage of the Pearl Harbor bombing in 1941 (confiscated and held for a year by the government).

A Town Remembers

The Historical Society whittled down the outtakes, added narrative and 1920s ragtime music, and created a short documentary—all running now on a kiosk at the Gilboa Museum.

"We cheated," Hudson admitted before screening the film to a packed house in nearby Conesville, another town impacted by the dam. "A typical newsreel would be one or two minutes. This is six. We were a little indulgent." Then the lights dimmed: "We're looking at the footage—the very, very last days of the village."

Why This Matters Now

The story of Gilboa isn't just history—it's about power, sacrifice, and what rural communities give up so cities can thrive. It's about resilience too. Gilboa rebuilt. The fossilized trees that were uncovered became a source of pride. And a century later, locals are reclaiming their story.

When a minister moved to relocated Gilboa a decade ago, she found people still processing the loss—still talking about streets and neighbors and lives submerged. The newsreel gives them something back: proof their town existed, mattered, and deserves to be remembered.

See It Yourself (or Listen)

The newsreel runs at the Gilboa Museum, open noon–4pm weekends from Memorial Day through Columbus Day, with special events year-round. Or listen now to Sue deBrujin’s ‘Two Country Lawyers and the Gilboa Dam’ here.

Root Access is your guide to life, work, and community in Schoharie County. Know a story that needs telling? Comment below!